In an interview with today's FAZ, French Foreign Minister Alain Juppé made the following, rather striking statement:

In an interview with today's FAZ, French Foreign Minister Alain Juppé made the following, rather striking statement:

“The dissolution of the eurozone is not acceptable, because it would also be the dissolution of Europe. If that happens, then everything is possible. Young people seem to believe that peace is guaranteed for all time…But if we look around in Europe there is new populism and nationalism. We cannot play with that.”This threat to peace is, of course, the justification for doing "whatever is necessary to ensure the cohesion of the eurozone."

Does Juppé really believe that people are still willing to buy into this transparent scare-tactic? He has simply turned the logic of current events on its head and confused cause with effect.

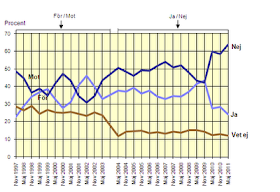

After all, the rise of populist parties, which Juppé cites as a threat to European peace no less, has been a response to the attempts to preserve the eurozone at all costs, with many of them using opposition to the bailouts to their electoral advantage.

The True Finns are perhaps the most prominent example of this strategy, which has both pushed them to the top of opinion polls and enabled them to influence the Finnish government from the outside. The argument over Greek collateral in return for Finnish bailout loans is a case in point. The protests against EU-backed austerity measures on the streets of Athens are another manifestation - the EU flag's 12 peaceful stars distorted by Greek protesters into a golden swastika should be enough to make us think twice. This tense situation is particularly damaging for Germany, which is now increasingly being seen as Europe's bully, reawakening some pretty unpleasant stereotypes.

The rise of anti-euro parties point to a situation in which the politics of the eurozone could become explosive. Juppé's polemic, and the mindset that gave birth to it, only makes such a scenario more likely. Shutting down or ignoring peaceful means of registering legitimate protest is the surest way to push people to extremes (though, just to be clear, populist parties around Europe are more diverse in their make-up and origin than is often understood, i.e. the True Finns and FPÖ are not the same). If voters' message is ignored, what options do they have left to register their opposition to and fears about the eurozone elite's consensus?

Former ECB board member Otmar Issing made the point in the FT earlier this month that:

"Any attempt to 'save' monetary union via agreements which transfer sovereignty to a European level, where violations of fundamental treaties have become a regular event, lacks any logic. In the end it will only further alienate the people from Europe itself...Similarly, in the FT this week, the standard-bearer of the German anti-bailout movement, Hans-Olaf Henkel, argued,

...This type of political union would not survive. Its collapse would be brought by resistance from the people. In the past cries of 'no taxation without representation' have brought war. This time the consequence would be to threaten the collapse of the most successful project of economic integration in the history of mankind."

However, with the fiscal union versus dismantling of the eurozone choice on the horizon (however distant) the politics of this issue are only going to get more fraught until politicians start addressing the genuine concerns of their citizens. Juppé's remarks are unlikely to help.